“Tristan da Cunha and the United Kingdom both have a major problem of self sufficiency”. This statement may seem to be bizarre, far-fetched or curious, but if we look at some of the facts and figures we can see that it is correct and not an exaggeration.

For anyone who knows about the island it would not be a big surprise to learn that Tristan does indeed have problems of self sufficiency. This is a tiny dot of a volcanic island, deep in the south Atlantic and some 1600 miles away from its nearest port of Cape Town. There are many factors that all contribute to it being difficult to produce a range of food crops on the island, and so a very large proportion of all the food consumed on the island has to be supplied through Cape Town. Also, fuel and medical supplies all have to be imported and if the supply chain is compromised the lack of these essential goods could become critical. As far as the UK is concerned, in spite of having one of the most advanced and capable agricultural systems in the world there has been a trend towards policy decision-making that has turned its back on the strategic and economic importance of the country producing its own food. As a result of these policies, spearheaded by Tony Blair when he was in power, the country’s self-sufficiency in food has dropped from 78% in 1984 to just 60% today. (This is calculated from a net import figure – imports less exports, and includes products that do not come to the table, such as livestock feed)

On Tristan, there are very few items that can be thought of as being available at a self-sufficient level. These are limited to fresh water, fish, mutton, beef and potatoes. Caution needs to be exercised when considering potatoes, because the annual crop is quite precarious. The crop is grown year after year on the same ground and naturally there is a build-up of diseases and soil-borne pathogens. Regrettably, a few years ago there were imports of seed potatoes from South Africa that were far from being disease-free, and in some cases yields from the ‘new seed’ were lower than yields from the islanders’ own saved seed potatoes. There is always the risk of total crop failure, and when it is considered that the potato crop is the only source of island-produced carbohydrate a crop failure could be disastrous.

In days gone by the people of Tristan da Cunha were successful in being virtually self-sufficient in foodstuffs, even having a surplus that they sold or bartered to passing ships. Since then the production of fruit and vegetables has greatly declined, particularly in recent years. One of the factors for this decline in food production, ironically, has been the development of the fishing industry on the island. This industry has resulted in eight ships a year now travelling from Cape Town to collect the catch, and it has resulted in the island having an income from the crayfish with which it can import a wide range of consumer goods, including fruit and vegetables. The import of these consumer goods has taken away from the absolute need to be self sufficient. As a result, individual gardens have largely fallen out of production and have been invaded by the New Zealand flax that makes such a good wind-break – but such a bad invasive weed.

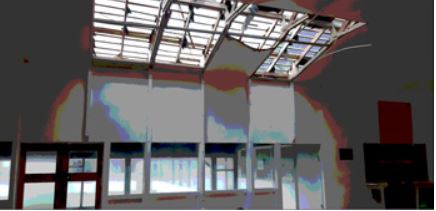

Vegetable production is difficult on Tristan – there are many factors that conspire to frustrate the would-be grower, including very harsh weather conditions and a wide range of slugs and insect pests that have arrived on the island and that have few if any predators. Also, it is not always realised that proper production can only be achieved with an active programme of care, including pruning, weed control, and spraying when appropriate. It is unsurprising therefore that many islanders now prefer to buy from the shop using their earnings that originate, essentially, from the sale of crayfish (“Tristan lobsters”) This is all well and good when conditions are normal, but the island risks a food security emergency when, as in 2020, the world is thrown into unusual circumstances by the coronavirus pandemic.

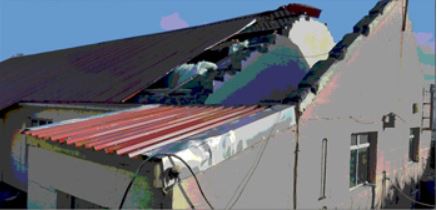

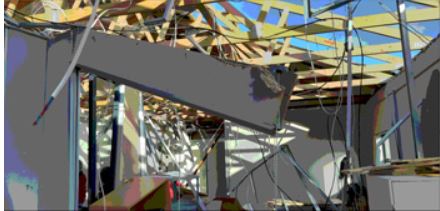

Around the time that the last ship arrived at Tristan, in late March, Cape Town was closing its doors to ships going in and out of the port, and to the supply of alcohol, fruit and vegetables. It became apparent on Tristan that the supply chain was going to be badly affected, and with great foresight the Island Council put in place a rationing system for essential foodstuffs. Even so, I understand that the shop warehouse ran out of rice, pasta and beer, and supplies of toilet rolls, milk, wine and other alcohols became perilously low. The next ship to make the journey, the Edinburgh, had its departure delayed several times, and it did not arrive at Tristan until 30 June. Even then the long-awaited stores could not be unloaded because of the sea conditions, and there were delays of 8 days and then 9 days while the ship sheltered from the weather. It was perhaps just as well that no fresh fruit and vegetables had been shipped, because it is probable that it would have all have become rotten and have to be dumped. Meanwhile, on another element of the same Covid 19 problem, the global marketing of the Tristan Lobster became difficult, and the island could no longer budget for the same income as before.

Even now, at the beginning of September, the supply chain problem remains. The next ship due to come out from Cape Town was due to leave on the 20th or 21st of August, but delays connected with the lockdown in South Africa have meant that the actual departure date has still not been fixed.

It is clear that the island has real problems of self sufficiency and of food security, and these problems have been highlighted and exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. One problem is that there is inevitably a considerable delay between an islander deciding to grow more of his own food, and actually being able to harvest his produce. It would take several years before an island population with a new-found interest in developing its self sufficiency could develop its garden land for efficient vegetable production. In order to improve the island capacity to produce its own vegetables, a couple of years ago it was organised to set up a seed-bank, so that seeds are permanently available to the islanders – unfortunately the seed-bank was never established and it is understood that there are no vegetable seeds to be found on the island. Seeds must be thought of as the beginning of the production process.

If we consider the UK, how can we possibly compare a country with a population of 66.65 million people, and the third largest economy of the world, with a tiny dot of an island in the Southern Ocean with a population of 245 souls? The problems of self sufficiency in the UK are not on the same scale as they are on Tristan, and on the face of it there are no problems of food security. (However, we are seeing unstable and uncertain times, and nothing can be ruled out)

In the last 40 years the UK has given away a large proportion of its agricultural turnover, by the nation buying elsewhere. Now, only 50% of the food that is eaten is home produced, with as much as 30% now produced in the EU. The facts behind these figures make gloomy reading. Over half of our vegetables are now imported, and over 300,000 tonnes of pasta a year are imported, 80% of which comes from Italy. Even 20% of our cheese and our beef is imported instead of being home produced. 1.2 million tonnes of potatoes are imported every year, as are 55% of the tomatoes we eat. We import 476,000 tonnes of apples every year, and 138,000 tonnes of pears. All of these, apart from pasta, are commodities that we can (and used to) produce ourselves. So, like Tristan da Cunha, our level of self-sufficiency has declined since the last war.

The situation with our apple industry is a typical example. France took huge EU subsidies to develop vast industrial-scale apple plantations in south west France. Our shops bought these low-cost apples, our shoppers were largely only presented with imported fruit, and the UK apple industry of Kent and Hereford was destroyed.

Apart from the political disregard for the strategic importance of our agriculture, and hence our self sufficiency, a number of other factors have come into play. A large number of immigrants have come into the country, bringing with them a taste for a range of foods that cannot be produced in the country. Our own interest in exotic foods has increased, partly triggered by a very high level of foreign travel. In an increasingly affluent society, we no longer like to be restricted to fruit and vegetables ‘in season’, but we are prepared to pay for them 12 months of the year. At the same time city centre and high-rise housing has been giving way to housing estates built on prime agricultural land, and increasingly the public has been developing the opinion that the countryside is for recreation rather than for food production. We even have ill-informed pressure groups who believe that the country should be covered with trees in order to achieve carbon capture and to save the planet – they either do not know or they choose to ignore the fact that well-managed intensive arable land captures 5 times more carbon than trees, by means of the soil being boosted with organic matter (humus)

We have seen that the coronavirus pandemic has changed the situation in Tristan da Cunha, and in the same way the UK is experiencing some changes. In the last five months there has been an increasing interest in home-produced products, and some of the supermarkets are increasing to launch promotions based on how much they obtain foods from within the UK. At the same time, there is a percentage of shoppers who are more and more discerning – they no longer want to be fobbed off by, for example, beef that is produced in the USA, Poland and elsewhere to far lower standards than the standards that are to be found on British farms (this is not blind patriotism, it is based on scientific fact). Another trend during lockdown has been the increased interest in people growing their own produce. If every household in the country set up three potato growing bags outside their houses, around 180,000 tonnes of potatoes would be produced every year! Clearly this is fanciful and could never happen, but it illustrates the potential for household production. In our garden in Scotland we have produced some 18 different species of vegetables and herbs – that is all stuff that does not have to be imported.