In order to try and describe how our life has been for the first four months on Tristan, I have to start by describing some overall details of this exceptionally remote island.

Tristan is a volcano, and quite a new one at that. Some 200,000 years ago there was the series of eruptions that caused the island to be formed in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. Thanks to the previous volcanic formation of some islands in the area (such as the tiny islands of Nightingale and Inaccessible) the ocean floor around Tristan is relatively shallow – only around 2,000 metres deep, as distinct from 4,500 metres deep over much of the Southern Atlantic.

Once the main landmass was formed, the forces of nature immediately started to attack the classic conical shape of an isolated sea volcano. Around the coast, wave erosion cut into the coastline, heavy rain caused erosion from the high ground, and at the same time new mini-volcanoes appeared, providing a complexity to the classical conical shape. This dynamic process is continuing to this day, and it will continue into the future. The 1961 eruption, which happened to be very close to the settlement of Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, was just a part of this dynamic process.

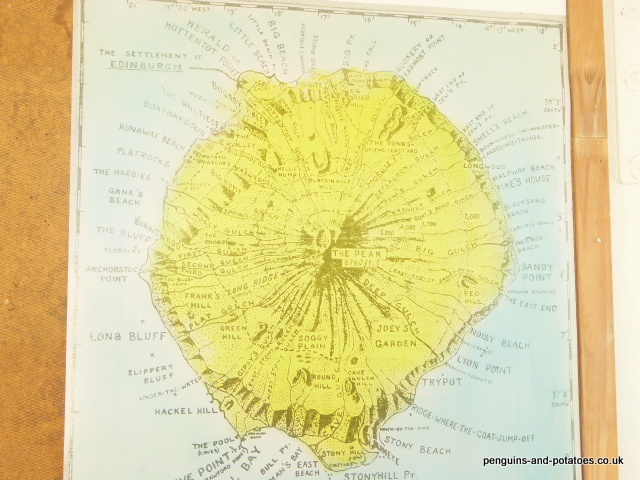

Tristan remains a classic conical volcano; the island is round like a clock face, and it is possible to pin-point features around the coast by reference to the clock. For example, Edinburgh is at 11 o’clock, Sandy Point is at 3 o’clock, Stony Beach is at 6 o’clock, and the Caves are between 7 and 8 o’clock.

The four places mentioned in the last paragraph are the four places where there is flat-ish ground and where there is some form of agricultural activity. In the past, particularly between the 1950’s and the 1970’s, there was quite a lot of agricultural work at Sandy Point – including the growing of potatoes, and the planting of apple trees and forestry trees (largely conifers and eucalyptus). Sandy Point enjoys a much more benign climate than the rest of the island, being in the lee of the strong prevailing winds, and the forestry trees have been very successful. However, access is the problem. There are no roads on the island other than on the Settlement Plain, and sea access is hazardous and only possible when the weather is right. In the past people made quite frequent journeys to Sandy Point, but now calm sea days are devoted to the fishing for crayfish and the men of the island have no time to tend the apples and to grow potatoes in this difficult terrain. I have been told that up to about twenty years ago, every year one day was designated as ‘Hapling Day’ (Apple-ing Day) and up to three longboats full of apples returned to the Settlement, but that is now all in the past.

Nowadays, the three outlying flatish areas are used for the grazing of cattle, which are very much left to fend for themselves. I have been lucky enough to go out to The Caves and to Sandy Point by joining teams of men going out to slaughter cattle for meat. In each case the process was much the same. The party set off in the ‘Government Launch’ with an oar-powered boat in tow. On arrival off the beach, the shore party transferred to the small boat and rowed ashore, leaving two qualified boatmen in the launch – it is not possible for the launch to land, and two men are needed for safety reasons. The islanders have enough experience of the hazards of the sea to have developed strong safety procedures.

When I went to The Caves, the oar-powered boat was taken ashore in relatively calm waters, but frighteningly close to the roar of breakers on a reef. The boat was beached at speed so that it rose up onto the gravel beach and as one the men jumped ashore, and we all pulled the boat up well clear of the water. Even with the boat high and dry two shore-lines were tied so that there was no risk of the boat departing on its own.

[Pic – LT2 – Caption = Our boat at The Caves]

The slaughter process was done with rifles, not unlike shooting deer. The cattle were pretty wild since they are never handled. Just one cow was shot, butchered, loaded up into big plastic bags and carried to the boat.

On the return journey, two men stayed in the small boat with the meat while the rest of us transferred into the launch. The men in the small boat were then able to handle the boat and tie it up when we were back in the harbour. For me, it was interesting and exciting to see the island from a different vantage point.

The second meat trip I did was to Sandy Point. I had read a lot about this place in Agricultural Officers’ reports dating from the 50’s and 70’s, and I was very anxious to visit it. The opportunity came up at short notice. On that day I had organised a Field Visit to our little Greenhouse project for members of the Agriculture Committee. When I started work at 6.30 that morning I learned that three of the five people expected would not be coming – they each had arranged to do more important things. I also learned that a boat was going to Sandy Point, departing in about an hour. So I cancelled the Field Visit, borrowed a lifejacket, picked up a bag with a sandwich (thanks to Bee) my waterproofs and a camera, and headed to the harbour.

The journey around the coast was uneventful, but the seas were higher than had been expected, and landing the small boat on shore was going to be challenging. The communication between the men on the oars as we approached the beach was interesting – voices were louder than usual and there was an evident tension. For the ‘final landing’ we made it – just! The boat was not maintained stern-on to the waves, and we broached. The starboard gunwale had six inches of water pouring over it, and most of the men ended up waist-deep in the water having exited the boat rather more quickly than they had intended!

I remained with members of the group until the steer was shot – that way they knew where I was and the risk of a shooting accident was avoided! Incidentally, I did notice that the procedures for gun safety were well developed and strictly followed. These are high-powered rifles, and when not required for cattle slaughter they are stored in the armoury in the Police Station.